What does it mean for a work of art to portray history? For a narrative medium like a novel or a film, the answer may feel obvious. The job of a good work of historical fiction is first and foremost to recreate for the reader or viewer what really happened. If the characters include actual historical figures, their actions must adhere to established fact and their thoughts and motivations must reflect what is understood of their personality. If fictional characters are created, they must be the type of people who could reasonably have lived in that place at that time, and their actions must not conflict with what is known about true historical events, though they may recontextualize and weave themselves around them. The text must be free of anachronisms and counterfactuals. But more than anything, a work of historical fiction must feel like real history, like it is opening up a window into the past. (Of course once you go beneath the surface, deep waters lurk; whose version of history are we actually portraying? After all, history is written by the victors...) However, when the medium in question is that of games or interactive fiction, things change a little bit. Playing a game involves making choices, and choices imply that there are multiple possible outcomes. Thus, when people play historical games, they are not just along for the ride, viewing the unfolding story from the perspective of already knowing how things turned out in the end. They are in the driver's seat; they are living history, and making the decisions that determine what kind of history actually gets made. Therefore, all historical games are inherently works of alternate history, a method of exploring the forces of history through the lens of process.

.png) |

| I am of course playing the dirty pinko commies. I've established a strong presence in Europe and the Middle East, but the Land of the Free is sneaking up on me in the third world. |

Twilight Struggle (all screenshots from the PC version) is a grand strategy board game in which players recreate the epic Cold War between the forces of liberal capitalist democracy, as championed by the USA, and the ideology of revolutionary communism that birthed the USSR. The game is played on a world map of interconnected countries, the network terminating in each of the two clashing superpowers. The players compete for control of these countries by building their influence points to a margin exceeding a certain threshold of stability. Each player has a hand of cards which have both an "ops" value and an associated historical event. Play proceeds through either spending those points for defined game actions or triggering the events, which have unique mechanical benefits. However, if a player uses an event card belonging to the opposing player for ops, they must allow their opponent to gain the benefit of the event, leading to a risky and calculating game of cat and mouse. Players may spread their influence slowly but peacefully, or they may take an aggressive posture, launching coups d'état to rapidly shift the balance in their favour. However, doing so may degrade the DEFCON level, reducing your options and making such dirty tricks less desirable, and if it is reduced from five to one the world ends in nuclear apocalypse (technically the player that triggered Mutual Assured Destruction loses, but in a truer sense, there is no winner). They may also compete for scientific and technological dominance in the space race. Players score victory points when cards are played determining the balance of power on each individual continent, with a net score of 20 or the higher score at the end of three phases of the war winning.

.png) |

| Making an aggressive move. I might have been better advised to headline Quagmire to bog the US down and save this card for its high ops value. |

Twilight Struggle has a well-deserved reputation as a stellar example of a perfect marriage of mechanics and theme, of using design itself to complement and communicate story and really make you feel as if you're living out the events you're involved in. The slow, cautious war of propaganda, diplomacy, and military brinksmanship shines through in the mechanic of grappling over abstract "influence" and "control", while the possibility of a region scoring at any time demands careful attention to maintaining supremacy on multiple fronts and guessing your opponent's intentions. There is a wealth of real historical information encoded in the event mechanics and the ideological map of cultural affinities and important battlegrounds, but the real meat of the game is in the feeling it evokes of being the men in the War Room, moving little pieces on a worldwide chessboard and scrambling to react to events beyond their control while gambling for the highest stakes imaginable. Winning and losing is usually an abstract matter of scoring points, but this is where historical context comes in; we know what a US victory looks like -- the Soviet economic and political system imploding, Chicago School ideologues going in to impose radical neoliberal "shock therapy", and Russia ending up as a pseudo-democratic kleptocracy ruled by a former KGB officer. And we can easily enough conjure to mind Soviet victory: the overthrow of capitalism by Marxism-Leninism and the spread of the "evil empire" to every corner of the globe.

.png) |

| Attempting a coup in South Korea. Little is said about the political administration I will raise up, or the oppressed masses who surely fought for my cause. |

And of course, while it hews closely to real history, Twilight Struggle is a sandbox for creating a counterfactual history of the Cold War. In the tutorial game for the PC version, the USSR attempts a coup in France, which to the best of my knowledge never actually happened. What if Canada went red? What if the ideological struggle in the third world were determinative of victory? What if Fidel Castro never overthrew the Cuban government? Things are necessarily highly abstracted from a narrative based in anyone's actual lived experience, but what the waxing and waning of such ideological regimes as the superpowers struggle for dominance would mean for the people on the ground can certainly be imagined. The players dance on the edge of Armageddon, carefully building small advantages to a tipping point, all while their citizens learn to duck and cover and pray that somehow this too shall pass. Though you are not perfectly reenacting the sequences of actual history, you are gaining some insight into what it must have been like, what it must have felt like, to live through such precarious and politically vertiginous times.

.png) |

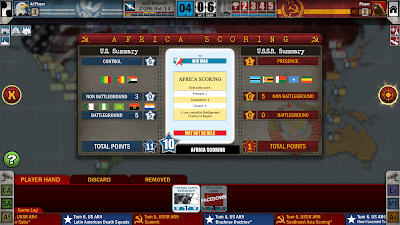

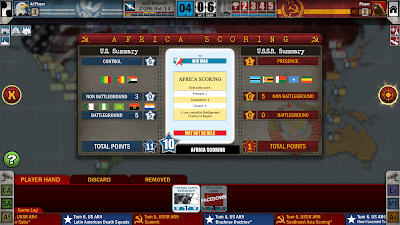

| I take an absolute beating in Africa. I guess McDonald's and washing machines are a more enticing inducement than proletarian anticolonial solidarity. |

One interesting mechanical note about Twilight Struggle, however, is its relative lack of attention to the actual ideological content of the political forces the two players are manipulating. Though the texture of the events presents different faces, and it is said that specifics of the event rules give the Soviet player an early-game advantage and the US player a late-game advantage, the gameplay rules for the two combatants are almost exactly the same. The tactics through which their political leaders are trying to drive events are what's important, the slow tug-of-war over institutions of power and ideological influence. The divergent methods through which the combatants' political and economic systems operated has no influence on which of them will win. It doesn't ultimately matter much whether you're a bourgeois parasite or a rabble-rousing Bolshevik, whether you believe in central planning or the invisible hand of the free market, whether you determine your leadership through contested elections or through diktat from the Party elite. All that ultimately matters is power.

.png) |

The only winning move is not to play. (Rest assured, I deliberately triggered this game state purely for the meme; I am not so unskilled as to have walked thoughtlessly into nuclear war.)

|

#

Labyrinth: The War on Terror, 2001-? (again, screenshots from the PC version) is a game that wears its design influences on its sleeve. Like Twilight Struggle, Labyrinth attempts to capture a historical moment in a bottle, a similar world-spanning conflict that was fought more on ideological than physical grounds. The card play system is lifted wholesale from Twilight Struggle and its successors, while the network of countries in boxes with governance trackers and cultural symbology will easily bring to mind its predecessor's game board. But Labyrinth certainly innovates on the formula laid down in its inspiration. It introduces pawns and a number of additional mechanisms to allow the two sides to be much more radically asymmetric. The US and Jihadist players play by a very different set of rules, as befits a conflict between an underground network of hidden revolutionary terrorists and a dominant hegemonic superpower with vastly superior resources, made clear (if it is necessary) by the fact that when the Jihadist rolls a die they want to roll low, while the US always wants to roll high. The Jihadist player is mobile and nimble, spreading Islamist cells throughout the world and dividing ops between multiple countries before massing to topple governments and institute fundamentalist Muslim theocracy, constantly losing advantage and taking risks but posing an ever-present threat of resurgence, while the US can deploy overwhelming and highly capable force, but moves far more ponderously and is heavily influenced by diplomacy and the winds of public opinion. The two countries are fighting over a single basic mechanism; the Jihadist must shift sufficient countries in the middle east to Islamist rule or "poor" governance, while the US must convince them instead to adopt "good" governance (which presumably means secular capitalist liberal democracies friendly toward the US). Muslim-majority countries may shift in governance and also in attitude toward the US, between ally, neutral, and opponent, while non-Muslim countries in Asia and Europe may shift in posture from "soft" to "hard", either aiding or hindering US capabilities (Israel's posture is permanently set to "hard", a rather chilling choice in view of more recent events). Jihadist funding is constantly eroding, restricting their hand size and the number of cells they can deploy, and they must stage relentless terror attacks to keep it high and exhaust the US's capability to respond, while the US can lose essential prestige if the game goes against it, imposing negative modifiers on die rolls, and similarly loses hand size if it deploys too many troops in the field and overstretches its military capacity.

.png) |

| Spreading my sinister cabal of moustache-twirling, "Allahu akbar"-shouting terrorists around the globe. My pawns are the black ones; make of that what you will. |

Labyrinth is of course a fever dream. Another decade and change on from the game's publication date, we now know that there was never a pervasive, omnipresent network of Islamic terrorist cells directed by a deranged mastermind like Osama bin Laden. 9/11 was a one-off, a historical fluke of the kind that sometimes sends the river of time spinning off in a wildly different direction. Occasional similar events were the work of lone-wolf radicals, not organized agents of a central master conspiracy. And the democratic regimes that the US imposed on the peoples of the middle east were built on sand; they were corrupt from top to bottom, and as soon as US occupation ended, the Islamists surged back stronger than ever. The War on Terror was a snipe hunt in which paranoid thugs in search of an enemy to justify their repressive ideology created one from whole cloth by invading and occupying nations which did not want them there. Many of the events and cultural forces portrayed on the cards are real, but others (like terrorists getting hold of a nuke or dirty bomb) are entirely fictional suppositions of what might happen. The game is too close to the events it is portraying to be informed by proper historical context. It is therefore not so much a simulation of actual history as an exploration of what history might have been like had this phantasm, this collective hallucination of a nation traumatized by a blow above all to their self-respect, been real.

.png) |

| The US convinces Pakistan to clean up its corrupt government. Notice that all European countries are permanently set to "good" governance. Their only role in the game is to support or oppose the war. |

One mechanical choice I would like in particular to call attention to is the fact that the US player has perfect knowledge at all times of where Jihadist cells are, even the hidden "sleeper" cells, and where and when they're planning terrorist attacks. In reality the US and their international coalition went to enormous effort trying to unmask terrorist cells and predict the next 9/11. That was after all what the PATRIOT act was about, the vast program of communications surveillance exposed by the Edward Snowden leaks, the torture and detentions without trial in Gitmo and Abu Ghraib, the invasive security screening now standard at every airport, countless intelligence-community honeypot operations that ended up fabricating more terrorist cells than they ever exposed. The lack of evidence did nothing but convince the investigators that the terrorists were just hiding even better than they had suspected. Since the priorities of the administration have shifted and the War on Terror had been put on the back burner, the number of Islamist terror attacks have not noticeably increased. In fact, White supremacists with legally-purchased automatic weapons have proved to be a much greater threat to public safety in the US than Muslim suicide bombers ever were. The threat of terrorism was both everywhere and nowhere, the massive wave of attacks portrayed in the gameplay of Labyrinth always immanent but never actually materializing. The only places where Islamists were actively blowing stuff up was places where US troops had come in and started acting like they ran the place.

|

.png) | | The US is facing strong headwinds; I have already significantly degraded their prestige, and the world is divided on whether to be hard or soft on terrorism. |

|

The word "quagmire" has been used to describe the War on Terror, but "labyrinth" is probably an equally good one. The US was lost in a maze with enemies around every corner and no way out. What is the victory condition of Labyrinth? At what point can we know that the threat of radical Islam is definitively beaten? You can't win a war on terror; there is no possibility of victory or defeat against an enemy that doesn't exist. It will continue to lurk in our public consciousness, inspiring the kind of irrationality that only the human mind is capable of. The euphemistic language of the War on Terror is embedded in Labyrinth; sending troops in to depose a government you don't like and replace it with one more amenable to your geopolitical interests is called "regime change", while using your soft power to influence the political institutions of other sovereign states is called a "War of Ideas". Given the original board game's rather glib title, I would like to think that this kind of thing is ironic. After all, by the time the game was published in 2010, Obama was in office and the problem of Islamic terrorism was already beginning to look less than urgent to the powers-that-be. It could be that Labyrinth is actually a farce, an attempt to poke fun at the US's self-important pretentions to being the saviour of liberal democracy. But if so, the mechanics of the game are played pretty straight. You, as the Jihadist player, can win the game by detonating a WMD in the United States. That feels like it's intended to be a pretty convincing argument.

|

.png) | I have succeeded in toppling the Pakistani government, giving the terrorists access to its nuclear arsenal. This is what Dick Cheney sees in his nightmares when he's eaten too much beef.

|

|

The big difference for me between Twilight Struggle and Labyrinth is that I was born just early enough for the fall of the Soviet Union to be one of my formative memories; to me, the events of the Cold War are a matter of history, though still of living memory. But I lived through the War on Terror. I experienced those events firsthand. I stood up personally and protested about the US invasion of Iraq. I saw the detainee-torture photos from Abu Ghraib on the evening news. I got in flamewars on the internet with people who thought that anything no matter how amoral was acceptable if it could prevent another 9/11. I was at a party once where a guy was saying "I keep hearing people speaking Arabic on the phone at the gas station, do you think they're terrorists?" and I reflexively responded "There are no fucking terrorists!" We knew that the War on Terror was a war of colonial aggression where the protagonist's own citizens were the enemy. We knew that the threat of terrorism was a bogeyman conjured up to justify imposing censorship and surveillance, to undermine democracy at home and abroad. We knew that the WMDs were fake. Labyrinth: The War on Terror is a piece of propaganda. It is pushing a narrative of a civilization besieged on every side by a shadowy existential threat that we knew at the time was nothing but an excuse. And sure, similar moral panics occurred during the Cold War. But at least the USSR really had nukes. At least the USSR really was fomenting political violence and lending military aid to authoritarian regimes. Whatever you may think of the ideological affiliations of Twilight Struggle, it portrays real history, not a confabulation based on phantoms and witch hunts and wounded pride.

.png) |

| Jack Bauer found the first nuke, presumably by torturing someone, but Mohammed had a second nuke hidden in his back pocket. Take that, western imperialist pigdogs! |

I can't help but wonder how a Muslim would see Labyrinth, how they would take the term "Islamist" being the opposite of the word "good" and the term Jihad, an intensely personal struggle against evil in the Muslim faith, used to mean "the process of using terrorism to install a repressive theocracy". I can't help but imagine how they would feel if presented with a game in which they must choose to play either a United States imposing its geopolitical will on the heartland of Islam or a demonizing caricature of their religion invented by fascists to justify autocratic overreach and the systematic violation of civil rights. And I can't help but wonder what great clash of civilizations the next board game in this sequence might reify. Perhaps the subtle and anxiety-inducing confrontation between the US and China? The fight against the worldwide rise of authoritarian pseudo-democracies and domestic fascist terrorists? Or maybe the struggle to prevent and reverse climate change, with one player representing a cabal of greedy industrialists fanatically pursuing personal wealth at the expense of the planet we live on and the potential extinction of the human race? Francis Fukuyama once notably offered us The End of History, the triumph of liberal democracy and a world of peace and prosperity forevermore. And yet history stubbornly refuses to stop happening. But at least if we play and critically analyze games like Twilight Struggle and Labyrinth: The War on Terror, we might learn enough to stop these global conflicts from ending in disaster. It's worth remembering that the precursors of the Taliban, and the viper Al-Qaeda that it suckled in its bosom, were armed and funded by the CIA to fight against the Russians in the Cold War. The decisions we make fighting one war can very well turn around and bite us in the ass during the next one.

.png) |

| Another case in which Labyrinth took inspiration from Twilight Struggle. Plus ca change... |

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment