If you're at all into the PC gaming scene, you've probably heard of Slay the Spire. This indie darling is one of those rare breed of games innovative enough to spawn a whole new subgenre of gaming: the roguelike deckbuilder; a game that almost immediately attracted imitations and riffs. And it did it in an interesting way: by raiding the unique innovations of tabletop gaming and making them its own.

Now, the importation of tabletop games into the world of computers is nothing new. Tic-tac-toe was among the first-ever games programmed on a computer, and every major tabletop game from chess to Monopoly to Catan has been reimplemented in digital form. Attempts to port the OG tabletop roleplaying game, our hallowed mother Dungeons & Dragons, birthed the immensely successful genre of the computer RPG (which itself was probably instrumental in inspiring the move of TTRPG design philosophy away from simulationism and toward the aspect of improvisational storytelling that a purely computerized experience can't yet replicate -- but that's another article...) Even physical sports were an early subject of computer games, though of necessity the approximations of the complex real-world physics and biology exploited by athletes were at best crude and limited. But Slay the Spire did something particularly novel: rather than merely copying an existing physical game, or building on it, or attempting to mimic an inherently physical process with computer graphics and sound, it remixed and reimagined a tabletop game mechanic in a way that maintained something of its inherently physical quality while expanding the possibility space of that mechanic in ways that only a computerized game can accomplish.

But let's back up for a second. Computers are one thing; physical chessboards and decks of cards are something very different. What is it that allows such productive cross-fertilization between the world of the tabletop and the world of pure information? How is it that the same game can exist in both media, and that game concepts from one media can so fluidly move to another?

.png) |

| Another doomed Ironclad sets out to conquer the dungeon. Good games present the player with interesting, consequential choices. |

To answer this, we're going to need to start with a little basic ludology. What is a game? What is it that makes a game what it is? This is an infamously difficult question to answer; some of the foundational texts of game studies were attempts to answer it, and it is even the subject of a famous philosophical thought experiment intended to demonstrate the impossibility of purely formal definitions. But of course academic discourse runs on definitions, so let's have a go anyway. If games are a form of art (a question that is itself contentious, though for the purpose of a blog like this I feel like it can be safely assumed), one way to go at it is to ask what defines them as an artistic medium, and I think the key there is an examination of how each different artistic medium is experienced. The literary arts are experienced by reading, the musical arts by listening, the visual arts by looking, the theatrical arts by watching (which might be considered a different process); dance, insofar as one participates in it, is experienced by moving, and one might stretch a bit and say that the gustatory arts (cooking and other methods of food preparation) are experienced by smelling and tasting. But a game is something that is necessarily experienced by playing.

.png) |

| Building my Ironclad's deck. Do I go for a powerful multi-attack, enhance the cards I already have, or debuff my enemies to make future attacks more potent? |

Play is of course something that is itself difficult to define, but a classic ludological angle is that play takes place in a metaphorical "magic circle" in which some of the everyday rules of society are replaced with a new set of rules that those who engage in the game agree to follow. While playing chess, one piece must be moved only in one way, a different piece in another. When playing Magic: The Gathering, there are intricate rules regarding what pieces of printed cardboard one may or may not assemble into a deck before one even begins a match. In an athletic sport, physically hitting other players in certain ways may be allowed, while other ways may be called "fouls" and incur penalties. Even in pure make-believe or the calvinball of impromptu children's play, there are rules, fluid and malleable though they may be. The the act of play is the act of following rules, not the rules of everyday society but a set of arbitrary rules which have been deliberately designed to produce a certain kind of experience. It is the act of making choices within the possibility space of what the rules allow, and of reacting to the choices of others within the constraints of the rules one has imposed on oneself. Thus, it is said in ludology that the defining feature of games is interactivity. Most forms of art are pretty passive, although of course the brain is always actively interpreting what it is passively experiencing, but playing a game requires the player to take action, to actively manipulate the game state, and usually to make choices under a condition of constraint.

|

| "Calvinball". Children instinctively create magic circles as part of the process of learning through play. Copyright 1986 by Bill Watterson; used under fair dealing. |

Art forms can also be defined in terms of their building blocks, the fundamental units of which a piece is composed. The fundamental unit of a novel is the word; the fundamental unit of a movie is the frame; the fundamental unit of a visual image might be the pixel or the brush-stroke. In this paradigm, the fundamental unit of a game is the ludeme, an abstract object which might be thought of as an atomic piece of rules. The pawn is a ludeme, and the fact that a a pawn's movement is limited, except under certain special circumstances, to one square forward is also a ludeme, as are the concept of squares and the number and configuration of squares that make up a chessboard. Given these definitions, it becomes easier to see how a game as an abstract system of rules can transcend the bounds of physics and reconfigure itself from the board and card to the computer screen. A game may incorporate artistic elements of many kinds, be they lexical, visual, tactile, or auditory (though few if any games incorporate taste or smell), but none of these are fundamental to what a game is. Every such element of a game may be changed, but as long as the rules themselves remain the same, it is still the same game (and games are in fact quite regularly "reskinned" in this way). Physical tokens can become images on a screen, but if the same rules are being followed, you are playing the same game. This is also what allowed games to take a quantum leap in complexity when people started using computers to make them. Computers are machines the entire purpose of which is to follow rules, so using them to make and play games is as natural a fit as any technological development in art history. Physical tabletop games or sports are limited in complexity by the ability of human minds to comprehend and execute the ruleset. With the computer taking on the task of automatic execution and enforcement of the rules, the possible complexity of game rulesets skyrocketed. It even became possible to program sophisticated rules for the simulation of other players, doing away with the necessity to play the game with other people and greatly expanding the possibility for solitaire game experiences, and even to make the game itself so complex as to be considered an opponent in its own right.

.png) |

| This run I'm going in for big attacks and cards that give extra energy to play more of them per turn. Time will tell if this is a winning strategy. |

The rules of a game, the sets of ludemes it employs and the ways in which they interact to create the overall product, are generally knows within game design and game studies as "mechanics". Games are an art form based in mechanics, and so game genres are typically defined in mechanical terms. Now for all its innovation, Slay the Spire's groundbreaking and genre-defining traits are a combination of aspects from two already-existing genres, one of them taken from computer gaming and one taken from tabletop gaming. It's right there in the name: roguelike deckbuilder; it's a hybrid of the genre of games known as roguelikes and the genre of games known as deckbuilders. To understand, then, what is so unique and unprecedented about Slay the Spire, we now need to ground ourselves in an understanding of what mechanical identities define these genres, what genre conventions they typically fulfil. Roguelikes are themselves a genre inspired by tabletop games, initially a subset of computer RPGs, though more recent takes have expanded the philosophy of the roguelike into new mechanical territory. The ur-text of the genre is obviously Rogue, a relatively simple game in which the player explores a dungeon and engages in turn-based combat with fantasy monsters in a quest for loot and experience. The fundamental innovation of Rogue itself, the novelty which made it the founder of its own subgenre, was the fact that the dungeon one explored was randomly and procedurally generated. Rather than being met with a dungeon explicitly designed by the game's creator, every time a player starts a game of Rogue they are met with a new dungeon with a unique layout, a unique set of monsters and items; they must adapt on the fly to the unique challenges that particular run offers. Another aspect of Rogue that became important to the mechanical identity of the genre that would become eponymous with it was the fact that once your character died, there was no going back, no "save scumming" and attempting to get a better outcome; the end was the end, and when the game was started anew, a new unique hero and a new unique dungeon were created, a mechanic that is now known as "permadeath". One does not learn to play Rogue, or any roguelike, by attempting the same process over and over until one succeeds as in many other kinds of video game. Instead, the player must learn how the underlying system works, and use their strategic skills and understanding of those systems to survive and triumph.

.png) |

| Rogue -- the game that birthed a thousand nails-hard die-a-thons. |

Now, on to deckbuilders. The deck of cards has a long history as a game piece, a technology for creating complex random outcomes within a certain set of combinatorial possibilities. Probably thousands of games have been implemented on a handful of multipurpose card decks, and new games started incorporating custom decks as printing technology became more sophisticated and less expensive. A revolution in game design occurred with the release of Magic: The Gathering, the first collectable card game, in which individual cards each containing their own set of ludemes from a large and ever-widening pool could be selected and combined by the player into a unique deck of one's own creation, making the player themself a partner in the game design process. But MTG in itself was not a "deckbuilder" as such. The honour of spawning this particular subgenre goes to Dominion, which innovated on the mechanic of building a unique deck with which one plays the game by bounding it and making it an active process within the gameplay itself. While one starts a game of Dominion with a generic deck of preselected cards, one is then presented in the process of play with a random assortment of cards which one may purchase and incorporate into their deck, as well as the opportunity to remove cards that one doesn't want. Through multiple hands from one's growing and repeatedly-shuffled deck, one combines cards to create an overall strategy for winning the game, a strategy that is unique to each playthrough while also responding to the overall system by which the deck is built and the game won. Perhaps now it becomes apparent in hindsight why the mechanics of deckbuilders and the mechanics of roguelikes are so compatible.

.png) |

| Dominion. I didn't buy enough money in the early game, and thus suffered when my opponent started monopolizing the highest-scoring estates. |

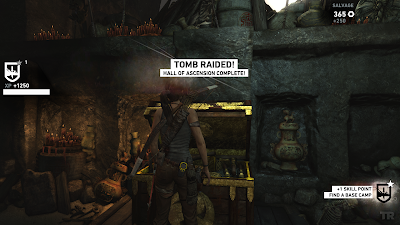

Thematically, Slay the Spire tells a simple story that is immediately familiar, though of course it is told with its own lore and nuance; a mysterious eldritch being is trapped in the bottom of a dungeon, and sends an infinite series of hapless champions up through that dungeon in an attempt to free itself. The gameplay is composed primarily of turn-based combat of a kind that will be familiar from many a CRPG; the player is given a set of moves to execute in an attempt to overcome an assortment of programmatic enemies. Some moves deal damage, some block enemy attacks, and some apply buffs or debuffs which give the player a future advantage. But the special sauce of Slay the Spire is the fact that your moveset is formatted not as a static menu or as skills with a cooldown as in most such games, but as a deck of cards. Every turn in combat, you are dealt a random hand from this deck which defines your options for that turn. You can only use your most powerful attack if it comes up in your hand for that turn, and if you happen to draw nothing but blocks, well, looks like all you're doing that turn is blocking. Thus, a mechanical style of combat which can easily become stale and tedious is transformed into a set of strategic choices made with limited and random resources. Luckily, enemies telegraph their coming moves, allowing one to make such choices a little more optimally. And as you play through a run of Slay the Spire, you will be building your character's deck in the same way one does in a game of Dominion. Though loot from killing monsters includes the usual gold, potions, and magical relics, every combat won also offers a random choice of cards to add to your deck. Each card has its own advantages and disadvantages, its own mechanical effects, and just as in Dominion, you are building your deck as you play with a strategy as to how you are going to win the game; the mechanics of the cards combine synergistically in a way that is unique to every playthrough, and early choices will influence which cards one wished to obtain later, or whether indeed one wishes to take any of the offered cards at all, given that the addition of new cards which may not fit the strategy will make the deck larger, and thus make the cards that one most wishes to have in hand less likely to appear.

.png) |

Spending my gold at the merchant. It's important to use the "card removal service" as often as possible.

|

Importantly, I think it's essential to the appeal of the genre that it maintains the metaphor of a physical deck of cards. There is no inherent reason that the moveset must be presented in this way, that the pieces of printed cardboard that inspired this mechanic could not be abstracted out of the picture. But a deck of cards is something familiar, something legible; almost anyone who has played any games at all knows how one works, and the concept of picking and choosing cards to build one from will also be familiar to those who have played Magic: The Gathering or similar games like Hearthstone, let alone specifically played Dominion or other games of its ilk. The new strategies involved in building a functional deck and successfully employing it in the new context of turn-based RPG combat are thus instinctively understood. But as a computer game, Slay the Spire can iterate on the concept far beyond what physical decks of cards and rulesets held within human minds allow. It can efficiently present you with a much larger pool of cards to choose from, and change the mechanical function of those cards on the fly. It can present you with a larger pool of randomized monsters, and automate the moves of those monsters, reducing the cognitive load of the player and allowing them to concentrate on the strategic choices the game offers. It can add things like relics and potions, a large pool of items which change the game in ways at least as important to your strategic build as the deck itself. It can track the details of your character between battles, and allow you to save your game so that the experience can extend itself until you either die and are sent back to square one or successfully slay the final boss and reach the game's win condition. It can do so much more with a simple deck of cards than something like Dominion ever could.

.png) |

| My strategy has worked out so far, but I'm in a bad state. Something tells me my quest will soon be over. Better luck next time... |

And this is what I find ludologically and even philosophically interesting about Slay the Spire. It is a showcase of the way in which mechanics in games both transcend and are embodied in the physical media which are used to create them. There is now a physical tabletop game based on Slay the Spire, but in its digital incarnation it could not possibly be anything but a computer game. And yet its central metaphor is still so stubbornly physical, so obviously still of the world of the tabletop in the same way that the digital implementation of Dominion itself is, and in a way that is so necessary to its identity as a game that those who have followed in its footsteps have largely maintained the metaphor intact. For all that they are implemented in the infinitely malleable medium of cyberspace, a simple deck of cards is so central to Slay the Spire and the genre it has created that it is difficult to imagine how a roguelike deckbuilder would work were this physical object not represented in it -- though of course it needs only the imagination and artistic craft of another game designer to create a fresh take on the mechanics which might even end up spawning a new genre of its own. But if the roguelike deckbuilder were to be transformed in such a way that it no longer required the representation of a physical deck, something essential to the magic and novelty of the genre would be irretrievably lost. How can it be a deckbuilder if you're not building a deck? That is a question that only future generations of gamers and designers can answer.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)