What does it mean for a work of art to portray history? For a narrative medium like a novel or a film, the answer may feel obvious. The job of a good work of historical fiction is first and foremost to recreate for the reader or viewer what really happened. If the characters include actual historical figures, their actions must adhere to established fact and their thoughts and motivations must reflect what is understood of their personality. If fictional characters are created, they must be the type of people who could reasonably have lived in that place at that time, and their actions must not conflict with what is known about true historical events, though they may recontextualize and weave themselves around them. The text must be free of anachronisms and counterfactuals. But more than anything, a work of historical fiction must feel like real history, like it is opening up a window into the past. (Of course once you go beneath the surface, deep waters lurk; whose version of history are we actually portraying? After all, history is written by the victors...) However, when the medium in question is that of games or interactive fiction, things change a little bit. Playing a game involves making choices, and choices imply that there are multiple possible outcomes. Thus, when people play historical games, they are not just along for the ride, viewing the unfolding story from the perspective of already knowing how things turned out in the end. They are in the driver's seat; they are living history, and making the decisions that determine what kind of history actually gets made. Therefore, all historical games are inherently works of alternate history, a method of exploring the forces of history through the lens of process.

.png) |

| I am of course playing the dirty pinko commies. I've established a strong presence in Europe and the Middle East, but the Land of the Free is sneaking up on me in the third world. |

Twilight Struggle (all screenshots from the PC version) is a grand strategy board game in which players recreate the epic Cold War between the forces of liberal capitalist democracy, as championed by the USA, and the ideology of revolutionary communism that birthed the USSR. The game is played on a world map of interconnected countries, the network terminating in each of the two clashing superpowers. The players compete for control of these countries by building their influence points to a margin exceeding a certain threshold of stability. Each player has a hand of cards which have both an "ops" value and an associated historical event. Play proceeds through either spending those points for defined game actions or triggering the events, which have unique mechanical benefits. However, if a player uses an event card belonging to the opposing player for ops, they must allow their opponent to gain the benefit of the event, leading to a risky and calculating game of cat and mouse. Players may spread their influence slowly but peacefully, or they may take an aggressive posture, launching coups d'état to rapidly shift the balance in their favour. However, doing so may degrade the DEFCON level, reducing your options and making such dirty tricks less desirable, and if it is reduced from five to one the world ends in nuclear apocalypse (technically the player that triggered Mutual Assured Destruction loses, but in a truer sense, there is no winner). They may also compete for scientific and technological dominance in the space race. Players score victory points when cards are played determining the balance of power on each individual continent, with a net score of 20 or the higher score at the end of three phases of the war winning.

.png) |

| Making an aggressive move. I might have been better advised to headline Quagmire to bog the US down and save this card for its high ops value. |

Twilight Struggle has a well-deserved reputation as a stellar example of a perfect marriage of mechanics and theme, of using design itself to complement and communicate story and really make you feel as if you're living out the events you're involved in. The slow, cautious war of propaganda, diplomacy, and military brinksmanship shines through in the mechanic of grappling over abstract "influence" and "control", while the possibility of a region scoring at any time demands careful attention to maintaining supremacy on multiple fronts and guessing your opponent's intentions. There is a wealth of real historical information encoded in the event mechanics and the ideological map of cultural affinities and important battlegrounds, but the real meat of the game is in the feeling it evokes of being the men in the War Room, moving little pieces on a worldwide chessboard and scrambling to react to events beyond their control while gambling for the highest stakes imaginable. Winning and losing is usually an abstract matter of scoring points, but this is where historical context comes in; we know what a US victory looks like -- the Soviet economic and political system imploding, Chicago School ideologues going in to impose radical neoliberal "shock therapy", and Russia ending up as a pseudo-democratic kleptocracy ruled by a former KGB officer. And we can easily enough conjure to mind Soviet victory: the overthrow of capitalism by Marxism-Leninism and the spread of the "evil empire" to every corner of the globe.

.png) |

| Attempting a coup in South Korea. Little is said about the political administration I will raise up, or the oppressed masses who surely fought for my cause. |

And of course, while it hews closely to real history, Twilight Struggle is a sandbox for creating a counterfactual history of the Cold War. In the tutorial game for the PC version, the USSR attempts a coup in France, which to the best of my knowledge never actually happened. What if Canada went red? What if the ideological struggle in the third world were determinative of victory? What if Fidel Castro never overthrew the Cuban government? Things are necessarily highly abstracted from a narrative based in anyone's actual lived experience, but what the waxing and waning of such ideological regimes as the superpowers struggle for dominance would mean for the people on the ground can certainly be imagined. The players dance on the edge of Armageddon, carefully building small advantages to a tipping point, all while their citizens learn to duck and cover and pray that somehow this too shall pass. Though you are not perfectly reenacting the sequences of actual history, you are gaining some insight into what it must have been like, what it must have felt like, to live through such precarious and politically vertiginous times.

.png) |

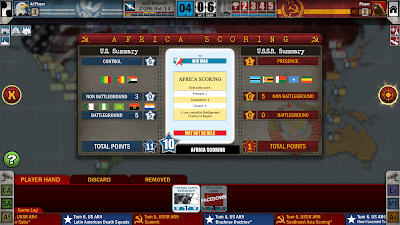

| I take an absolute beating in Africa. I guess McDonald's and washing machines are a more enticing inducement than proletarian anticolonial solidarity. |

One interesting mechanical note about Twilight Struggle, however, is its relative lack of attention to the actual ideological content of the political forces the two players are manipulating. Though the texture of the events presents different faces, and it is said that specifics of the event rules give the Soviet player an early-game advantage and the US player a late-game advantage, the gameplay rules for the two combatants are almost exactly the same. The tactics through which their political leaders are trying to drive events are what's important, the slow tug-of-war over institutions of power and ideological influence. The divergent methods through which the combatants' political and economic systems operated has no influence on which of them will win. It doesn't ultimately matter much whether you're a bourgeois parasite or a rabble-rousing Bolshevik, whether you believe in central planning or the invisible hand of the free market, whether you determine your leadership through contested elections or through diktat from the Party elite. All that ultimately matters is power.