Within the first several minutes of Tomb Raider, Lara Croft is nearly drowned, impaled on a spike, and has to fight off a man that, if you are not quick-thinking and agile, will kill you with a handmade axe in an intensely intimate fashion.

For a male action hero, this is all in a day's work. We would not even blink to see a man subjected to this kind of violence in a movie or video game. But when it's a woman -- especially a frightened, disoriented woman inexperienced in facing violence -- things get a little more complicated.

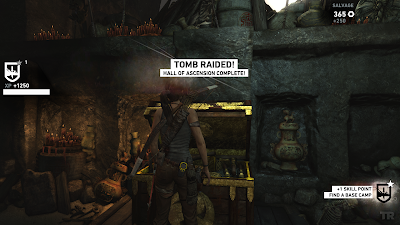

I'm sure that Tomb Raider needs no introduction. This critically acclaimed reboot of a franchise going back to the 90s shows the origin story of famed archaeologist Lara Croft. While striving to live up to the legacy of her dead father, Lara and a boatload of comrades are shipwrecked in the Dragon's Triangle and wash up on an island which is the former home of an ancient Japanese god-queen, and the present home of an insane cult hoping to resurrect her. Mechanically, it's set firmly in the grand tradition of its forebears, a third-person adventure game involving traversal, shooting, puzzling, collecting, and of course the inevitable quick-time events. Priority is given to immersion; there are no health bars, precise gear loads are obfuscated, and the inevitable RPG elements are cloaked in a descriptive veneer to hide their naked mechanical advantages. It's a pretty linear experience, predating the open-world live services that are popular these days, and it has a difficulty level that makes it accessible to even a filthy casual like me. All in all, I'd say it deserves its reputation as one of the best games of the decade; I had lots of fun with it.

|

| Facing off against a squad of cultists. Some things never change. |

For years, Lara Croft was held up as the icon of Feminism in gaming, a badass chick that could hold her own against the likes of Doomguy and Duke Nukem. There was even talk of how playing as a strong female character like Lara could serve as a role model for girls and make teenage males steeped in the toxic macho culture of gaming more sympathetic to the plight of women in society. But in recent times, the discourse around female characters in media has changed, and the designers of Tomb Raider quite plainly took some of those ideas on board when reinventing this iconic gaming franchise.

The most immediately apparent difference between 2013's Lara Croft and her 1990s namesake is that she's less... she doesn't have such... she isn't as... there's no polite way to put this: her boobs aren't as big. Not A-cups by any means, but not pornstar-sized either; reasonably proportioned. That's hardly the most important change, but it does seem to encapsulate the direction in which the devs have chosen to go when reinterpreting the character. Lara has also lost a lot of the sass and wisecracking nature of her hyper-competent forbear. She's hardly a shrinking violet; in addition to being a trained archaeologist, she's athletic and competent with a bow, able to easily climb rock faces and leap off of crumbling bridges. She also has an innate survival instinct, translated mechanically into the ability to highlight important environmental objects, that will serve her in good stead in the coming trials. But here at the beginning of her career, Lara is not the flippant and frankly mannish globetrotting superstar of the franchise's earlier (and later) outings. She has emotionally vivid relationships with other characters, and projects a kind of vulnerability that makes the terrible things that are happening to her deeply threatening in a way that games rarely really accomplish. She is just a relatively normal young woman who finds herself in a bad situation and has to do whatever she has to, learning to kill and to survive under the harshest of trials.

|

| It would hardly be Tomb Raider if you didn't get to raid some tombs, now would it? |

And that's kind of a problem, because mechanically, the game doesn't really keep up with this change in mood. One minute Lara is almost puking after having to shoot a man for the first time; the next she's gunning down armies of cultists with practiced ease. She wails and gasps at every new terror, yet takes dozens of bullets with barely a wince. She is motivated by her interpersonal relationships to pursue goals with deep urgency, yet is willing to take time off at any given moment to track down collectibles and infiltrate ancient ruins -- her deep scientific curiosity getting the better of her, I guess. This makes for a rather schizophrenic experience, as the story the devs want to tell about an average woman having to overcome adversity and survive against all odds butts up against the gamer fantasy of going HAM on an island full of bad guys. I'm not saying it makes the game bad, but it does kind of undermine the idea that this is a new Tomb Raider for a new generation of women gamers, that this Lara Croft is a realistic portrayal of a female character with a deep interior life, that the bad old days of a woman built like a stripper cracking one-liners with a gun in each hand are gone.

My wife absolutely loathes Lara Croft and Tomb Raider. She hates the fact that for years, such a blatant sex object was pointed to as proof that the industry and gaming culture was not sexist -- let us remember that Lara's infamous bustline was the result of a programming error that was loved by adolescent playtesters -- and she has told me that the aftertaste of years of seeing women in gaming portrayed this way has permanently soured her on the franchise. She is not going to play the new Tomb Raider; she is not going to experience the growth in the way the developers think of women as characters. When you make a bad enough first impression, it's not good enough sometimes to make amends and beg forgiveness later. The damage has been done.